The Life of a Tragic Artist: A Study of Vincent van Gogh’s Mental Health

by Ella Hang, 2025-2026 Student Executive Committee Member

January 28th, 2026

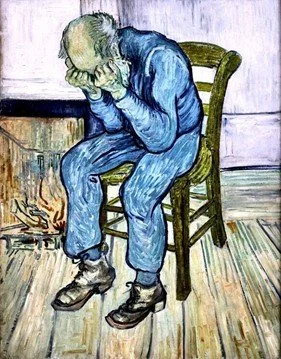

Van Gogh's Sorrowing Old Man (At Eternity's Gate) (1890)

An old, frail man is sitting in a chair. His feeble figure, clothed in blue, is bent over in a position of pain and despair, awaiting his death. The room around him is empty and bleak, save for a small fire in the corner. Two months after painting “At Eternity’s Gate”, also known as “Sorrowing Old Man” (1890), Vincent van Gogh was found dead. The dying old man depicted in the painting was an unsettling reflection of Van Gogh’s final months, in which he spent most of his time isolated in the Saint-Remy asylum. However, the tragic and untimely end of Vincent van Gogh’s life was not a unique case of an isolated artist’s mania and illness. Mental health issues have been prevalent in the artist community for centuries, with some of the most prominent cases being documented in the 18th century by Francisco Goya and William Hogarth through their artwork. While being an artist does not guarantee mania or mental instability, external factors such as financial stability and public opinion as well as internal factors like personality and lifestyle play a large part in contributing to mental health issues.

There is strong evidence in Van Gogh’s letters that he lived in poverty for most of his life, which was primarily due to his poor success with the public and fellow artists during his lifetime. His paintings themselves did not fit into the Impressionist style of the time and were crafted in a “more bold and unconventional style” leading him to sell very few of them to the public (“The Challenges of Vincent Van Gogh”). This failure resulted in almost complete and utter reliance on his brother’s funds, as he had no income whatsoever. To his brother, he wrote, “It really bothers me that I have so little success with people in general, I’m very concerned about this, and all the more so because rising above it and getting on with the work is at stake here” (“Van Gogh Letters”). Unfortunately, his luck with fellow artists was no better. Van Gogh famously cut off his own ear after a psychotic break and argument with his friend, Paul Ganguin, resulting in his hospitalization in Saint-Remy Asylum and his isolation from the outside world. With only a single sale to his name, a reputation of mania, and an unpopular style, Van Gogh’s artistic future seemed hopeless. But despite all this, he still managed to produce over 2,000 artworks with the help of his brother.

The stark difference between Van Gogh’s vibrant colors in his famous series of paintings Sunflowers (1887-1889) and Monet’s famous Impressionist art, Impression, Sunrise (1872).

Vincent’s perpetual lack of money, even with his brother’s funds, was not due to the fact that he received so little but that he spent it so rapidly. His life was “a life of expenditure, because he was selling nothing” (“Van Gogh Letters”). He spent his money on paints and canvases from Paris, tobacco, alcohol, gas lamps, and visits to the brothel. Despite the assistance he received, it simply was not enough to support him. With his lack of sales, Vincent had no means to repay his brother, despite numerous promises that he would. Feeling guilty, he wrote, “The money that painting costs, that crushes me under a feeling of debt and cowardice, and it would be good for that to stop if possible” (“Van Gogh Letters”). The constant stress of dwindling money and the guilt of not being able to repay his brother led Vincent to experience depressive episodes, which he attempted to numb with alcohol and tobacco. He remained trapped in a cycle of poverty, guilt, depression, and addiction, resulting in an unhealthy lifestyle that only amplified his existing problems.

Van Gogh’s excessive spending on art supplies left very little for basic necessities, such as food. His diet consisted of an extreme consumption of alcohol, coffee, absinthe, and more often than not, nothing. Even in his productive weeks, “he lived off 23 cups of coffee and the odd crust of bread” in the span of an entire week (“Art Net”). His already fragile personality and unstable mental state began to deteriorate due to guilt, stress, and obsession, resulting in rejection of food and excessive drinking to drown out these intense emotions. He constantly “deprived himself of sleep with abusive amounts of tobacco and coffee” to support his sudden bursts of mania disguised as a spark of inspiration (“Vincent van Gogh’s Sleep”). These sleepless nights often led to him becoming dazed and having frequent hallucinations. The pressure to succeed and his constant deprivation of basic human needs to prioritize art culminated in multiple mental breaks, leading him to flirt with the idea of suicide.

It’s important to note that throughout Van Gogh’s entire life, he was plagued by intense emotions and possibly even underlying personality disorders. These aspects of his life were made more volatile as he submerged himself deeper into his unhealthy lifestyle and obsession, later becoming a cause of his social rejection. In his early years, his emotional sensitivity was prominent, being a distinct factor of his life. He was described as “a moody child, self-willed, and often annoying” (“The Illness of Vincent van Gogh”). Even as an adult, he stated that he was “a man of passion, capable and prone to undertake more or less foolish things which I happen to repent more or less” (“The Illness of Vincent van Gogh”). This unwavering passion often led him to stay up late for hours on end, starve himself, and let his body go to waste in the name of creating art. This heightened his already intense mood swings, resulting in increased manic and depressive episodes. As he grew older, his typical consumption of absinthe resulted in partial seizures, which slowly worsened and sprouted off into other issues, such as chronic epilepsy and psychosis. His seemingly minor attributes as a child, coupled with his detrimental habits, evoked his inflammatory mannerisms and manic behavior.

Despite Van Gogh’s numerous struggles with mental health, substance abuse, and poverty, he is still regarded as one of the most valued artists of his time. His unwavering passion and complete commitment to his unique style required him to sacrifice and struggle with so much because he truly believed in his value and contribution to the art world. Nowadays, “In a world that often values conformity, Van Gogh stands out as a beacon for those who feel like outsiders” (“Beyond Van Gogh”). Through his immense emotional turmoil and struggle, he used his art to “express his inner world” (“Exploring Lessons From Vincent van Gogh”). His passion for his art may have overwhelmed his ability to live comfortably outside of it, but each stroke on the canvas allowed him to escape his real life, full of stress and instability. It allowed him to express his complex emotions and understand himself. His raw, bold art inspires countless artists today, impacting the art world more than he could have ever imagined.

Works Cited

“390 (393, 328): To Theo van Gogh. Hoogeveen, on or about Wednesday, 26 September 1883. - Vincent van Gogh Letters.” Vangoghletters.org, 2024, vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let390/letter.html. Accessed 17 Dec. 2025.

Art, Claire. “St. Claire Art.” St. Claire Art, 2014, www.stclaireart.com/abstract, https://doi.org/10f17558728/1052.

“Biographical & Historical Context - Vincent van Gogh Letters.” Vangoghletters.org, vangoghletters.org/vg/context_3.html. Accessed 6 Dec. 2025.

Blumer, Dietrich. “The Illness of Vincent van Gogh.” American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 159, no. 4, 1 Apr. 2002, pp. 519–526, ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.519, https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.519. Accessed 13 Dec. 2025.

Finsel, Elaine. “Sorrowing Old Man (at Eternity’s Gate) · ENGL-105 Digital Art Exhibition.” Orourkes.omeka.net, orourkes.omeka.net/items/show/165. Accessed 27 Nov. 2025.

Kryger, Meir H. “Vincent van Gogh’s Sleep.” Sleep Health: Journal of the National Sleep Foundation, vol. 9, no. 5, 1 Oct. 2023, pp. 567–570, www.sleephealthjournal.org/article/S2352-7218(23)00158-4/fulltext, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2023.07.011. Accessed 13 Dec. 2025.

Monet, Claude. “Impression, Sunrise.” Etsystatic.com, 1872, i.etsystatic.com/18641759/r/il/0982d3/3854750965/il_1080xN.3854750965_7ag7.jpg. Accessed 13 Dec. 2025.

Parra, Rosella. “The Challenges of Vincent van Gogh and How They Impacted His Work.” ArtRKL, 17 May 2023, artrkl.com/blogs/news/the-challenges-of-vincent-van-gogh. Accessed 7 Dec. 2025.

“The Last Days of Vincent van Gogh.” Van Gogh Museum, www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/art-and-stories/stories/the-last-days-of-vincent-van-gogh. Accessed 7 Dec. 2025.

van Gogh, Vincent. “Sunflowers.” Wikimedia.org, 1888, upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/46/Vincent_Willem_van_Gogh_127.jpg/960px-Vincent_Willem_van_Gogh_127.jpg. Accessed 13 Dec. 2025.

walker@paquinentertainment.com. “The Enduring Popularity of van Gogh: What Makes His Work so Famous - beyond van Gogh.” Beyond van Gogh, 14 Nov. 2024, beyondvangogh.com/the-enduring-popularity-of-van-gogh-what-makes-his-work-so-famo. Accessed 9 Dec. 2025.

---. “Why Vincent van Gogh Was the Ultimate Outsider in Art - beyond van Gogh.” Beyond van Gogh, Nov. 2024, beyondvangogh.com/van-gogh-was-the-ultimate-outsider-in-art/.

Whiddington, Richard. “Art Bites: Van Gogh Once Subsisted on Coffee and Bread.” Artnet News, 19 Apr. 2024, news.artnet.com/art-world/art-bites-van-gogh-coffee-and-bread-diet-2448774. Accessed 13 Dec. 2025.